Making a Synthetic Cell

Observations and ideas for how to build life from the bottom up

Relationships with Reality

What if we could build life from scratch? I don’t mean natural reproduction or cloning, but actually generating living organisms, de novo, from raw materials? How would we know that it was living, and what would be possible if it was?

These questions have been on my mind for quite some time now, especially as I dive deeper into replacement approaches in the brain. What is the difference between a living neuron and an electrode of a brain computer interface? What is the difference between a “cell-free reaction system” and a “living” cell? Such delineations might seem arbitrary if they serve the same purpose, but I think this difference is the key to unlocking a new era in human biology.

Computers revolutionized our relationship with electricity. What was once just a current on metal could be coerced through silicon to complete complex calculations. Although the earliest forms of this manipulation took up entire rooms to do relatively simple math, it wouldn’t stay that way for long.

The natural progression of that engineering led to coding software programs that took electrical currents and transformed them into our wildest imaginations. With AI, these currents are now being manipulated to mimic our own behavior so convincingly that it is replacing human interaction for some people.

Manipulating Biology

Despite our adeptness at manipulating electricity, we actually have a relatively limited toolkit for manipulating biology. At this point, I will acknowledge that biology is much more complex than physics, that it wasn’t until recently that we actually knew our own genome, and that many people are working on this.

But for the sake of this argument, let’s put that aside for a moment.

There is a code to life. Each of us is simply an amalgamation of hardware (cells) running a very complicated software (DNA) that executes programs (doing all of the things we do). This is as true of humans as it is of E. coli. The three elements here are 1) the hardware, 2) the software, and 3) the output.

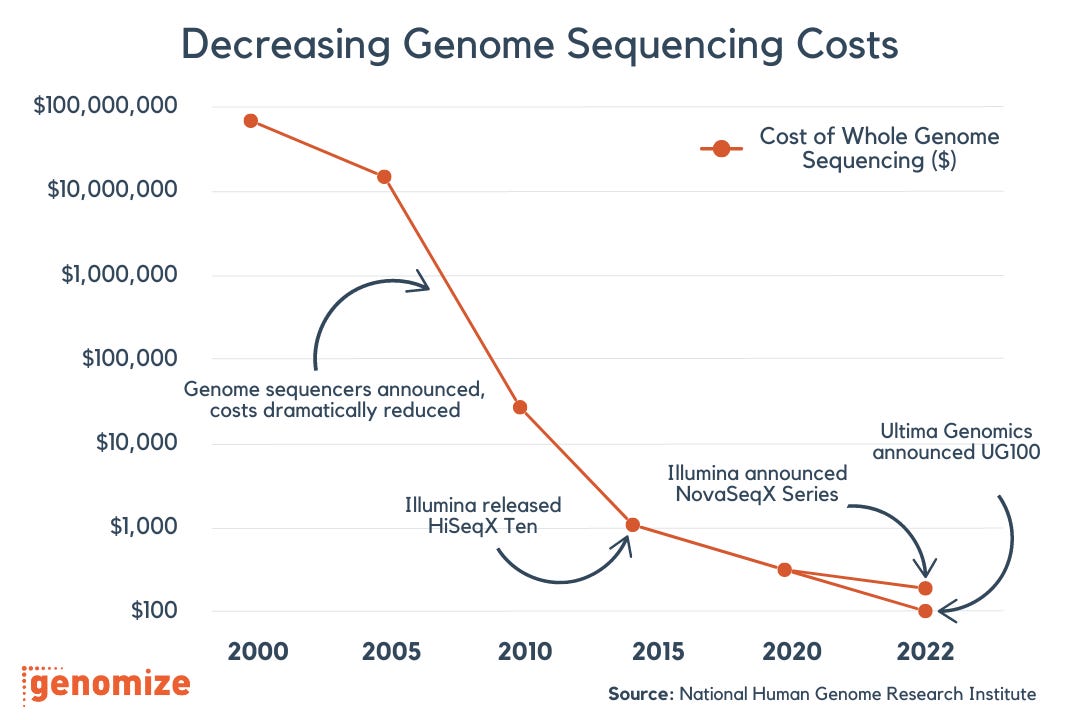

In my (humble) opinion, the bottleneck for manipulating biology (and thus driving discoveries) isn’t our ability to read and write the software anymore. We’re actually really good at that now, just take a look at how much genome sequencing costs have dropped in just two decades.

I think the challenge lies in a combination of two factors beyond the software: Our limited understanding of the hardware we are working with and our limited ability to write code that works well with said hardware.

So what if we could change not only the software that encodes our programs, but also the hardware that is running it? You could have written the entire codebase to structure and train GPT-1 back in 1960, but if you were trying to train that on an IBM 360 mainframe… good luck, see you in 60 years.

More importantly than speed is the rules of engagement. The nice thing about computers is that we (someone) knows exactly how it was made. Every circuit, every screw, every wire, every chip; The entire construction of the system and how it is supposed to work was blueprinted out by humans long before you turned on the power.

For biology, that’s not the case. To this day, we are still trying to understand the vast complexity of cellular pathways, how gene expression is regulated, even why and how we die sooner than some organisms, but later than others. While we’ve made great progress on mapping some elements, we’re a far way away from a blueprint.

Don’t take my word for it, just ask the CEO of the first trillion-dollar biotech company with a nation-state level R&D budget:

“And today, I don’t know, I would estimate we might know 10 to 15% of human biology,”

- David Ricks, CEO, Eli Lilly (On the Cheeky Pint Podcast)

Yikes.

But what if we didn’t have to keep stripping down and building back up just to even get a sense of what is going on in our complex cells? What if biology could be just as “neat” as computer architecture? If building computers from the bottom up enabled us to rapidly innovate…

What if we could build biology from the bottom up, as well?

Synthetic Cells

To do this would take a herculean task of synthetic biology. But, in my estimation, we have the tools, talent, and time to do it. The fundamental elements are there: genome reading and writing technology, expanding knowledge of gene regulation elements, and generative datasets to approximate how genetic sequences influence protein translation and function.

While these elements might not be perfect, we have enough of a grasp to “program” simple genetic circuits to serve our needs. If we can combine enough of these together, we could theoretically build the blueprint for a de novo living cell.

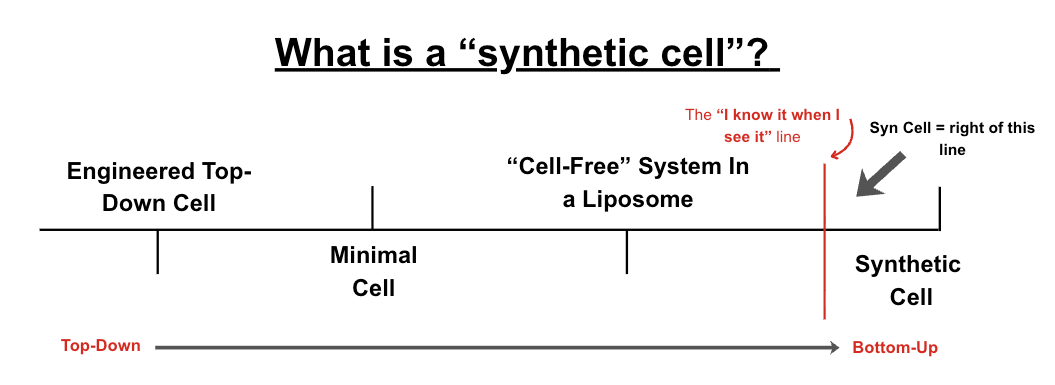

But what counts as a “de novo synthetic cell”? It’s a slippery continuum, even among scientists at the vanguard. Similar to how discussions on consciousness tend to dissolve rapidly into definitional hell, synthetic cells suffer the same gap.

So, to dodge that problem for the sake of this piece, I am going to define some ground rules/definitions on which I am operating. In my view, when we say “de novo synthetic cell”, we are referring to a “thing” with:

A membrane (is contained and partitioned off)

Genetic material (or some other “code”)

Functionalization of that code (does not have to be “transcription/translation” as we think of it currently)

Reproduction capacity (does not need to be autonomous or sexual, can be triggered by an external intervention and asexual)

Bottom-up assembly and is NOT assembled from large strings of existing genetic elements like a minimal genome (can borrow, but not copy)

These elements are not infallible, though. As a fallback, I borrow the best rule of thumb from Dr. Kate Adamala (who herself borrowed this quote from a SCOTUS Justice): “I know [a synthetic cell] when I see it.”

In this regard, I am excluding really cool things like minimal cells, top-down engineered cells, and cell-free expression systems. These are really useful for growing our blueprint of biology, but aren’t, in my opinion, true to the nature of “bottom-up” construction of life in line with the analogies above.

The Value of De Novo Life:

Bottom-up genesis of synthetic cells entails immense potential for biomedical, agricultural, and more (on top of ethical responsibilities). These cells, just like computers, can be designed with the end goal in mind. Rational design could guide the creation of living machines with features tailored to specific purposes: curing diseases, creating energy, growing food, and protecting us from pandemics.

Imagine what 2050 would look like if we could actually design synthetic cells: Things that sounded impossible today become commonplace. Many diseases, spanning autoimmunity, cancers, and neurodegenerative conditions, are all much better managed thanks to these cells serving as in situ drug factories and living monitors.

Meanwhile, synthetic cells are playing a meaningful role in slowing climate change, capturing carbon, and cleaning polluted air. Bottom-up biofactories are generating wood-like fibers from waste products, powering a boom in sustainable housing production.

Synthetic cells are even transforming the battlefield, equipping forward operating bases to endure long missions with limited supplies. Compact “foundries” produce purpose-built cells on demand from written instructions, right there on the field, with simple ingredients. These custom cells can manufacture food, clean water, and even construction materials on-site, all from dirt, air, and sunlight. This greatly reduces reliance on complex logistic chains that are susceptible to interception and collapse.

And that’s just the beginning. Trying to brainstorm all possible applications of bottom-up cells misses the point of the innovation, though. It would be like trying to predict every single website/tool that could be made when inventing ARPAnet.

The value of de novo life is in how it changes our relationship with the predictability of biology. The fact that we are the masters of the blueprint turns biology from a test of understanding into a product of engineering. No more guess-and-check, just build-and-test.

Starting Simple: Building a Chassis (FRO Idea)

Building de novo synthetic cells is much easier said than done, though. And, just like computers, the first version will look nothing like the rest. However, with something as resource and talent-intensive as synthetic biology, it is helpful to make the first shot on goal something widely applicable to maximize the number of translational opportunities.

Just like with computers and phones, adoption will likely meet resistance. Why use Google Maps? Just learn how to read a real one. Why have all your contacts on your phone? Just remember the numbers. So on and so on.

Therefore, building a simple chassis is a wise strategy. ChatGPT wasn’t initially built for a given target audience or application; it was a general “chassis” LLM on which piles of wrappers have been built for specific purposes. I envision synthetic cells coming to life (pun intended) much the same way.

However, this approach makes translational incentives difficult to navigate. Academia is often focused heavily on publications and definitional alignment. Although there is great work happening in labs and consortia across the globe, there are a lot of vectors pointing in different directions at this point.

Founding a startup on this tech is also difficult, regardless of the eventual target market. Market forces push companies towards incremental progress in the engineering of existing cells. If synthetic cells are the equivalent of building a car from scratch, VCs are often looking to invest in “faster horses.” Mature companies, such as pharma and biotechs, face a similar dilemma. They are built to hit targets with known or marginally altered modalities. This means that a synthetic cell chassis would be unlikely to outcompete the profitability of iterating on existing modalities to tackle a new target.

Before innovators or big players begin to take advantage of the enhanced predictability provided by synthetic cells, we must first develop the fundamental ability to generate them; that is, a chassis.

Doing so will likely take the form of a nonprofit. I am a fan of the focused research organization (FRO) model, which can coordinate cross-disciplinary talent (geneticists, cell biologists, material scientists) to align on a clear goal in a time-bound fashion. The cherry on top is this model’s emphasis on building partnerships to carry the fundamental technology towards application across many disciplines, maximizing its potential. If we want to build a synthetic cell, I am skeptical it will be done (soon enough) under current academic or market dynamics.

Just like the internet, just like Saturn V, and just like the Human Genome Project, building a synthetic cell will not happen with profit or publications as the incentive.

What Now?

First we need to get serious about definitions. While people may disagree on where the exact line is drawn between living and non-living, we need to set a list of ground rules. Once those ground rules are set, we can begin to amass the talent, capital, and partnerships needed to bring it to life.

What I do know is that now is the window to make this happen. We finally have a convergence of the enabling technologies to transition from guess-and-check to build-and-test. Focusing on a chassis could ensure that developing a synthetic cell is not only possible, but widely impactful for society. In this piece, I only briefly mentioned the ethical implications of this work, but there are many serious considerations (like mirror life) I didn’t address. I will save those thoughts for another piece as this one is long enough and defer to people with much more credibility to speak on this than me.

If you’re interested in this idea and want to talk more about what an FRO for synthetic cells could look like, I’d love to talk! The bottleneck here isn’t imagination, it’s alignment.

Love this!

is this similar conceptually to bnext.bio?